It’s not even 10am, yet many people gathered at the Carriageworks market in Erskineville have been awake since dawn. Stalls of organic vegetables and ethically sourced pork chops take advantage of the steady foot traffic. A man juggles the curiosity of his ten-month-old Labrador while trying not to crush the bunch of peonies he’s just bought. They are perhaps a peace offering for his disgruntled wife, following behind with their hoard of sticky children.

There is a single-file line for bacon and egg rolls that stretches far beyond the stall’s designated area. As people shuffle closer to their orders, the smell of bacon floats through the air in complementary coexistence with the soft sounds of a solo cellist. As someone who has played for nearly ten years, I don’t need to see the musician to recognise the instrument’s singular deep tone. Around the corner sits Haydn Skinner, a 91-year-old cellist. Skinner’s Saturday morning performances are a weekly occurrence at Carriageworks, bringing a sense of calm that balances the flurry of activity.

Isabel Rondoni, an Erskineville local and regular at the markets, nurses a soy cappuccino in her hand. Like the rest of the people in line for Sonoma Bakery’s signature loaf, she watches the cellist.

“He’s here every week,” Rondoni says, a smile forming across her face. “He lets little kids hold the bow and play with him. It’s pretty cute to watch.”

People weave between the queues and stalls of produce, eyes glued to their phones. Their focus shifts between deciding what filter to apply to the gluten-free pastries on their Instagram-story, and trying to secure a free table in the sun, a hot commodity in this frosty weather. Skinner plays to an audience of diverted gazes and AirPods, but with the same passion and precision found under the bright lights of Carnegie Hall.

As I approach the solo cellist, my eyes are glued to his fingers. They seemingly move with a mind of their own, no longer relying on practice and concentration.

He asks me what pieces I like to play, and as I list my favourites, he plays each one in full. He begins the opening notes of Camille Saint-Saëns’ Le Cygne, arguably one of the cello’s most recognisable and beautiful pieces. His fingers glide along the A-string with distinguished grace, landing perfectly where each note demands. Le Cygne does not boast speed or force, but rather earns its stamp of difficulty from the distinct clarity and tuning required to produce the right sound. The pace of Saint-Saëns’ melody dips and darts at the mercy of the weathered hands controlling it.

Skinner plays each familiar adagio, andante, and nocturne without breaking eye contact once. It’s as though he’s speaking a language only I, as a fellow cellist, can understand. As he plays, the sheet music that balances on his flimsy stand is open to another piece by Bach, one he played earlier. The notes on the page are irrelevant. Haydn Skinner plays with perfect muscle memory, embedded in his brain from a lifetime of experience.

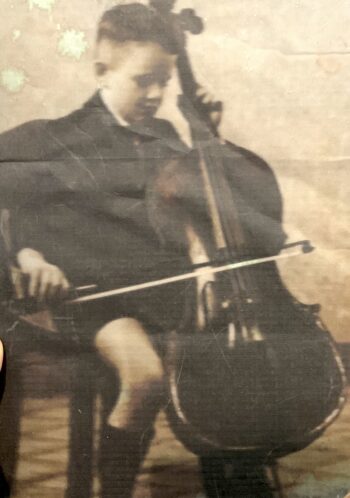

Skinner, 1939. Photo: Supplied

He follows my gaze toward a small black and white photograph sitting in his open cello case, held down by the loose change of grateful listeners. The aged picture shows a small child, knee-high black socks and all, mastering the grip of his cello. The stern sense of concentration on the young boy’s face is palpable.

“That’s me when I was eight-years-old,” Skinner remarks at the photograph, fondly. “That’s when I started!”

It may have taken 83 years, but the small boy in the photograph most certainly grew into the shape of his instrument, and socks.

Skinner’s personal Instagram account, @haydnnothidin, is a clever quip playing on the pronunciation of his name. The cause of such phonetic confusion? Franz Joseph Haydn, the renowned Austrian composer. Haydn has been dubbed the Father of the String Quartet, a title of endearment recognising his contribution to classical music. Closer to home, Haydn Skinner, a father in his own right, uses the social media platform to post uplifting excerpts of his market performances.

Raised in Sydney’s western suburbs, it seems Haydn Skinner’s musicality has been embedded in his DNA since birth. His mother, a talented pianist, instilled in him a profound interest in the works of great classical composers. Both Skinner’s sisters played and later taught the violin, and their father conducted several choir groups. On leaving secondary school, with a myriad of successful Eisteddfods and musical accolades to his name, Skinner decided against pursuing the cello professionally at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. Instead, the gifted musician studied medicine, eventually relishing in an extensive career in Obstetrics at Parramatta Hospital.

This year, in addition to three children and seven grandchildren, Skinner will celebrate sixty-five years of marriage. His other love, his cello, continues to remain an integral part of his life. During our conversation, he lists the names of the orchestras he’s played with throughout the decades on his two hands, very quickly running out of fingers as he counts. At age 80, when most retirees would revel in the gentler prospects of retirement, Skinner pursued a new cello teacher, persistently sharpening his skill and broadening his musical repertoire.

Reflecting on his medical career, and his decision to retire at age 67, he candidly admits with a chuckle, “I didn’t know I’d make it to 91!”

His wit and sharp humour sing out nearly as loudly as his instrument. For each piece he plays, there is a musically-themed joke about the name of a composer that follows. The delivery of his puns land with subtle comical timing, loyal to his sweet and cheerful character.

“Did you hear about the composer that died?” Skinner asks with a smirk. “He did his best work decomposing.”

When he plays the final chords of Bruch’s Kol Nidrei, a tragically sombre Adagio, he hands me the same bow he’s used since 1938.

“It’s your turn now,” he says matter-of-factly, standing up to stretch his legs. “I’m going to get my coffee.”

Cello bow/sheet music. Photo: pixabay

There is no denying the beauty of his cello, every sense captured and heightened in its presence. She boasts the figure of a Grecian goddess with a tonal range that puts Frank Sinatra to shame. Even from a distance, one can smell the residue rosin as the bow glides across the four strings. The nearly 300-year-old wooden frame stands as an example of a standard of craftsmanship no longer practiced.

Skinner’s cello is magnificent: to the ears, eyes, and nose alike.

Even in its largest size, a cello often looks comically small when encompassed by a grown man’s body. In front of Skinner, the instrument’s hourglass shape stands its ground, supporting the weight of his wearied body. To the untrained eye, the instrument he is holding mirrors a piece of worn-out junk stashed away in your grandparents’ garage to gather dust. But today, thanks to a combination of inflation and heightened demand for historical craftsmanship, a 250-year-old cello in its original condition is essentially worth as much as a deposit on a house. Hardly junk.

Similarly, much like a three-bedroom family terrace that is walking distance from the nice end of Oxford Street, the value of this instrument will only increase with each passing year.

Today the Beecroft Orchestra, situated in Carlingford, is lucky enough to hear Skinner play regularly. An ensemble of predominantly string instruments, this self-sufficient community orchestra consists of passionate adult musicians from all sorts of professions.

While sharing her own fond opinions of Carriagework’s in-house cellist, Beecroft’s Dr Susan Allman details the dedication of all the orchestra’s members, emphasising how the last 12 months of COVID restrictions have impacted performance opportunities for musicians like Skinner.

“We are self-funded, so we’ve really struggled over the last year,” Allman explains. “Membership numbers have dropped given the pandemic, and we weren’t able to put on any concerts, which is where we make the money to support ourselves.”

As fate would have it, we are speaking 24 hours too late. One of the Orchestra’s rare public concerts was held the previous afternoon. On our second meeting the following weekend, Skinner recounts that additional cellists were brought in to assist his section in performing the set repertoire of Brahms and Beethoven, as the orchestra simply couldn’t meet the expectations of such famous works with its regular deteriorated numbers. Beecroft’s upcoming concerts are listed on their website, allowing the public to attend and show their support for passionate and experienced musicians like Skinner.

Asked about Skinner’s impressively persistent talent, fuelling his musical ability well into his nineties, Dr Allman shares my inspired sentiment with the added perspective of a practised GP.

“He’s quite deaf as you probably know,” Allman states blankly, her tone comfortably switching to that of a consulting doctor. “He wears a cochlear implant.”

Like his weathered instrument, one might say that at 91, Skinner too has lost some of his varnish. Until speaking with Allman, the veteran cellist’s hearing loss had not been obvious. Perhaps an impressive example of his musicality and memory, his deteriorating hearing and various other physical ailments rarely affect the quality of his playing today.

Carriageworks performance. Photo: Instagram@haydnnothidin (Lea Jobson)

He joked with me about the callus forming on his right index finger, a complaint any outdoor cellist knows all too well. It’s from the pressure he is forcibly applying to his bow, trying to compete with the sheer volume of his surroundings. The chatter between passers-by and competitive vendors almost mimics a crowded aviary. With so much movement and noise, it is hard to believe Skinner doesn’t feel a sense of discouragement. But performing to an audience is not his intention here. Whether the entire market gathered to listen, or no one at all, he would play with the same passion and skill that he has since he was a boy.

Hidden deep in the tangled web of the internet remains a digitised copy of The Fortian, a magazine celebrating the yearly achievements of Fort Street High School students. In the 1945 edition one brief reference stands out.

There, in dated black ink on page eleven, 15-year-old schoolboy H Skinner is congratulated for his moving performance of Le Cygne. There are nearly 80 years between Skinner’s high school debut, and the rendition I witnessed at the markets, yet the steady melody of Saint-Saëns’ masterpiece has remained unchanged. How many times has this cellist placed his well-rosined bow firmly on the A-string, taken a grounding breath, and played that first tranquil G?

In the penultimate movement of Saint-Saëns’ Le Carnaval Des Animaux, the titular swan has floated through decades of musical interpretations and cultural portrayals as the most stubborn of creatures, resisting the inevitable effects of ageing. The intertwining musical melodies of Le Cygne present both sides of the swan’s identity. The swift and steady piano accompaniment alludes to the power and urgency of the swan’s paddling below surface. Amidst this urgency, it falls under the cellist’s responsibility to convey the swan’s floating grace. The solo cello’s melody draws on the creature’s striking stillness, a picturesque image of beauty above the water’s surface.

Perhaps Skinner feels a sense of serenity and likeness within the story behind the music, recognising parallels between the swan and himself. With his age catching up on him, grasping at his mobility, strength, and hearing, he is still able to find moments of undisputed beauty through his cello.

Taking a step back, I watch the frenzied crowds inside Carriageworks weave around the cellist once more. A child no older than five stops next to Skinner’s cello case, mesmerised by the deep tone of the instrument’s lower register. Holding his mother’s hand, the other gripping a flaking croissant, the child listens tentatively. In no time, he forgets the half-eaten pastry in his free hand and his preceding determination to return home.

For as long as his mother’s patience will permit, he will happily watch the man with the cello.